Feature: China's Octogenarian Forecaster

Date:2020-03-23

China's top science award winner Zeng Qingcun delivers a speech during an annual ceremony to honor distinguished scientists, engineers and research achievements in Beijing, capital of China, Jan. 10, 2020. (Xinhua/Shen Hong)

by Xinhua writer Yuan Quan

BEIJING, March 23 (Xinhua) -- At 85, Zeng Qingcun, is still looking for better ways to keep up with the speed of weather changes.

Recognized by many as the world's top meteorologist, Zeng, for more than six decades, has been studying the Earth's atmosphere and its changes. He is a pioneer of numerical weather forecasting; has developed infrared remote-sensing theory for meteorological satellites; and made scientific contributions to disaster risk reduction.

In recent years, Zeng has focused on climate systems and promoted the construction of the Earth System Simulator in Beijing. It is a world-leading giant facility that can simulate the Earth system and forecast climate for years, decades and beyond.

Such visionary research on global climate and environmental change has come under the spotlight on World Meteorological Day, which is marked annually on March 23 and has the theme Climate and Water this year.

When Zeng started working on meteorological research in the 1950s, the world's weather and climate forecast services were inadequate.

Photo taken on Nov. 29, 2014 shows a portrait of Zeng Qingcun, a meteorologist from the Institute of Atmospheric Physics under the Chinese Academy of Sciences. (Xinhua/Jin Liwang)

He chose meteorology as a career after his childhood experiences of seeing people suffer due to meteorological hazards for which they were unprepared.

He was born into a poor peasant family and grew up in the countryside in south China's Guangdong Province. He learned to do farm work and was aware of the difficulty in weather forecasting when he was young.

He remembered his parents looking up at the sky every night, expecting to predict the next day's weather from the dark sky and praying for good weather to bring them a harvest.

In 1954, an extreme overnight frost froze about 40 percent of the wheat in the main grain-producing province of Henan, destroying harvests and hurting the economy.

"If we could have forecast the weather and taken precautions, we could have reduced the losses," he recalled.

After graduating from the Peking University, Zeng went to the Soviet Union to study in 1957. Encouraged by a teacher, he tried to apply physical-mathematical thinking to enhance the accuracy of weather forecasts and decided to choose numerical weather forecasting for graduate study.

However, his classmates and other teachers thought he was crazy. Numerical forecasting required a huge dataset and very complex calculations, which many scientists found too daunting.

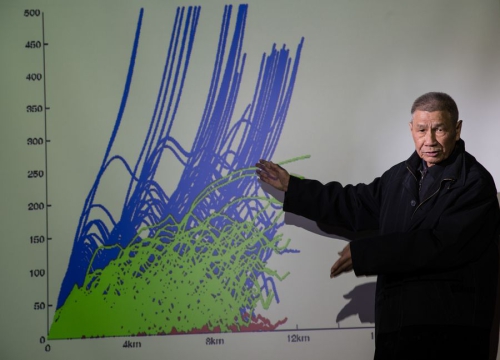

Zeng worked hard, often forgetting food and sleep. In 1961, he published his dissertation in Russia, sharing a method he created, called "the semi-implicit scheme," which uses primitive equations to approximate atmospheric flow and predict short-range weather. At that time, an experienced forecaster could only make regional forecasts 24 hours in advance.

His method is still used today.

Zeng returned to China in 1961 and became a researcher at the Chinese Academy of Sciences. He used the momentum from the numerical weather forecasting in satellite meteorology, a research program that China started in the 1970s. Zeng was a lead researcher.

The program led to a book in 1974 on how his team discovered that infrared channels for the remote-sensing of water vapor content in the upper levels of the troposphere can provide clear pictures of weather phenomenon such as typhoons and heavy rains, as well as monitor weather-related geological and hydrological disasters such as landslides and flooding.

The findings, though theoretical, influenced the design of China's meteorological satellites and have been widely used Chinese meteorologists to provide government decision-makers with disaster risk alerts.

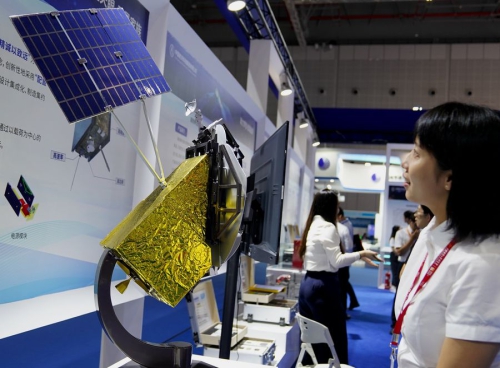

China launched its first meteorological satellite Fengyun-1 in 1988 and now has launched a family of 17 Fengyun satellites into space.

The Fengyun-2H meteorological satellite, carried by a Long March-3A rocket, is launched from the Xichang Satellite Launch Center in southwest China's Sichuan Province, June 5, 2018. (Xinhua/Liang Keyan)

In 2014, with the help of a Fengyun meteorological satellite, Chinese meteorologists accurately forecast the landing time and location of super typhoon Rammasun 24 hours in advance. The Fengyun satellites also worked well in monitoring and forecasting dust storms.

Zeng's work brought him international acclaim, and a host of accolades, including the World Meteorological Organization's top award, the IMO Prize, in 2016.

In January this year, Zeng was presented the country's top science award for his scientific research.

Zeng is proud of his contributions, but regrets spending so little time with his family due to work.

In 1987, when Zeng was working on the Fengyun satellite program, his elder brother fell ill and died. For a long time Zeng blamed himself for not taking better care of him.

A visitor views a model of Fengyun-4 satellite during the 2019 China International Industry Fair in east China's Shanghai, Sept. 17, 2019. (Xinhua/Zhang Jiansong)

China's meteorological services have made huge progress. China has taken the global lead in the number of meteorological satellites, which provide data to more than 80 countries and regions.

More new-generation Fengyun satellites are scheduled for launch, and the Earth System Simulator is expected to be built in 2022.

"The current technologies can already forecast weather over the next few days or more, but they are incapable of predicting the climate over the next few years," said Zeng, who now aims to track the speed of climate change.

"The Earth System Simulator will fill a gap and help us to understand more about changes in global climate and environment," Zeng said. "When it is completed, I must go to the site to have a look."